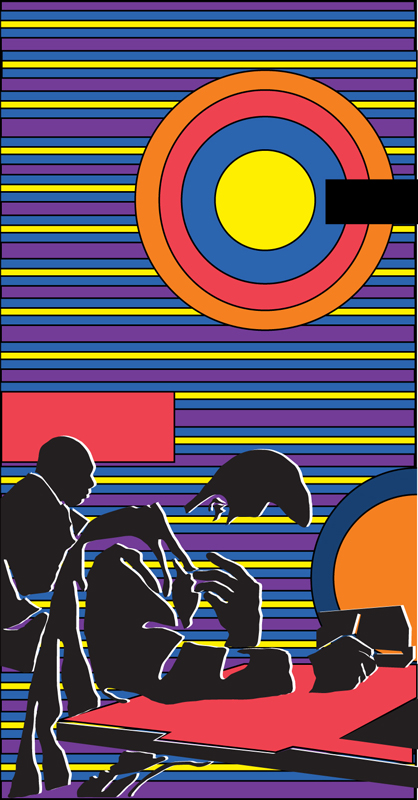

Carceral Archipelagos (2019): Inmate, Digital study for vinyl and silkscreen banner.

In Carceral Capitalism, author Jackie Wang asks the question, “How can we imagine ourselves out of a box that we don’t even know we are stuck inside?” I read this book as I began work on a new series of artworks, Carceral Archipelagos. Wang’s question challenged me when I read it, and it vexes me still. The simple answer to it is that art is how: Through a variety of processes, art can show us the frames and the boxes, then let us step outside them to bring something new into existence.

Yet it is not that simple. In her essay On the Pain of Others, Susan Sontag admonishes that, “ No ‘we’ should be taken for granted when the subject is looking at other people’s pain.” Sontag is right. The boxes that we want to imagine ourselves out of are filled to their brims with people’s pain. No “we” can be assumed—no common understanding, no shared belief, no agreement on principles can be taken for granted. Each of us brings our own truths to our viewing, reading, hearing, experiencing of an artwork. Therefore, I as an artist have an awesome responsibility to forge a “we” where it does not exist, through the crucible of art.

The slippery concept of truth stands in the way.

The first definition of truth is simple: in accordance with fact (verifiable). I can use my artist’s tools of form, medium, process, technique to present facts, like these: In the U.S., more than $100 billion is spent each year to support and sustain keeping more than 2 million persons under supervision, including incarceration. Incarceration is the main form of punishment in the U.S., which has the largest prison population in the world, and the highest per-capita incarceration rate.

Carceral Archipelagos (2019): Digital studies for vinyl and silkscreen banner: (1) Ex-Offender, (2) Defendant, (3) Protester, (4) Peacekeeper, (5) Offender.

It is in dealing with the second definition of truth on which we slide: reality —the world or the state of things as they actually exist. We have different lived experiences, different narratives of pain, different realities. I may feel that the U.S. wastes money keeping individuals shackled and locked in cages; you may feel differently.

Thus, to forge a “we”, I as an artist take up the creative problem of telling and investigating truth. Brecht wrote that there are five difficulties in truth-telling: (1) courage to tell the truth, (2) keenness to recognize the truth, (3) skill to manipulate the truth as a weapon, (4) judgement to select those in whose hands the truth will be effective, and (5) cunning to spread truth among many. I use form, medium, process, technique to recognize, tell, manipulate, and spread truth(s). The corollary to truth-telling is truth-listening or truth-seeing, about which Brecht did not write. To forge a “we,” I also take up that. Art gives us a seemingly easy way into difficult, complex, well-constructed boxes, like the box of the carceral state. Through art we can step into questions of power and its uses/abuses, our unique positions within systems, our roles and complicities. If we linger with, in, and around the box, we look carefully and deeply, and we begin to see things that we didn’t see before. We find juxtapositions that can lead us to ask questions about what we see, why we see it that way, and whether others see it as we do.

What if the criminal justice system functions as it is intended?

What does the ever-growing U.S. police state say about US?

What does it mean for “the people” to be the victim of a crime?

How do we measure the action of feeling sorrow and regret for having done wrong?

Truth-telling and truth-listening require critical thinking, critical feeling, and critical reflecting. To forge a “we,” to imagine ourselves out of a box, both I as an artmaker and you as an artviewer need to really see the box, contemplate it, and seek to understand it. If we make it that far, we can connect that box to our own boxes. Only then can we decide to deconstruct or climb out of those boxes. Only then can reconciliation occur, and only then can we begin the journey to becoming sound or healthy again.

It may be too much to ask of art.

© Santa Fe Art Institute / Santa Fe, New Mexico /

© Santa Fe Art Institute / Santa Fe, New Mexico /