It was unexpectedly fitting that on the last evening of my residency at SFAI, I met artist and historian Nell Painter and took part in a panel discussion with her and other residents about making art and maintaining resilience in the art world. Dr. Painter’s highly acclaimed book, Old in Art School, lifts this veil of secrecy by recounting her own experience with unhelpful (and at times unprofessional) art teachers who were dismissive rather than appreciative of student efforts, with one teacher telling her “You will never be an artist.” I admire Dr. Painter’s honesty and agree with her that making art is a process—of doing work and learning—not a state of being.

I came to SFAI with a project on Truth and Reconciliation, visualising and materialising the 99 Australian Aboriginal deaths in custody investigated by the Royal Commission in the 1990’s. I started my residency with a great deal of hope—here was my opportunity to create artwork without the incessant demand of my academic day job. However, I also felt trepidation because my own art school experience taught me that many artists can be competitive to the point of being destructive, protective of their ideas, and reluctant to share their success stories or failures.

During my initial meeting with Toni Gentilli, SFAI’s Residency Program Manager, she encouraged me to play, to work in both poetry and multi-media, and to explore complex feelings of my own personal ethnicity and culture, and the sense of not belonging. She asked me to listen to the “yes” voice within myself, and to take risks.

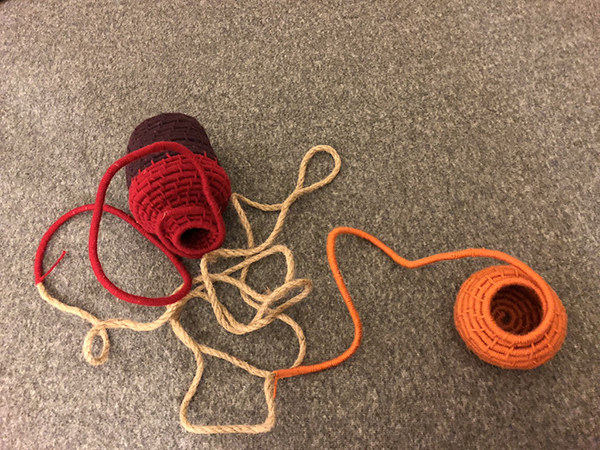

For more than 15 years I have practiced art while also conducting research and writing scholarly articles about creativity. I have been very critical of our culture’s current privileging of novelty as I have seen how it often leads artists to creating personal brands and narratives about the distinctiveness of their work. While at SFAI, I was seeking a more authentic and transformative artistic practice, and I soon found that working with material helped to get my non-rational brain going. Even though I’ve been working with digital media for the last ten years, I bought lots of yarn and wrapped trees, rocks, and ropes, re-igniting my interest with fiber and reconnecting with projects I started over 35 years ago. There was something about the organic feeling of branches, roots, and tubers that I felt connected with.

I soon established a working routine: first I would write a short poem on whatever came to mind, then I would sketch or draw an image, and finally I would make something physical. It worked surprisingly well. Through my writing, drawing and making, I was building connections to memories of my family, the history of Chinese people in Australia, and aspects of the history of Native people in America. I started knitting a scarf with the yarn I bought, and continued knitting whenever I had time, feeling a re-connection with my mother, who was a great knitter. I began writing poems about the losses I felt, feeling that this would help me tell my truth and reconcile my past with my present.

What I found at SFAI, to my surprise and delight, was an extraordinary level of camaraderie and generosity among residents. I got to know the other eleven artists through formal presentations, informal chats, sharing a cooking and eating space, and the occasional social get-togethers. Most important of all, I was inspired by their varied approaches to making art.

The work of fellow residents Frida Wu, Ssu-ya Hsuing and JeeYuen Lee prompted me to experiment with performance art. With the help of Ssu-ya, I staged a performance of being tied up with a 100-foot rope to a tree in the SFAI courtyard. For 70 minutes, my body became one with the trunk of this leafless tree, outside with no shelter against the elements. I felt utterly exposed and quite vulnerable. Towards the end of the performance, I found that I had developed a strange attachment to the tree, as it gave me a sense of warmth and steadiness. Without warning, I became quite emotional. I realized that my father, who died when I was an infant, was named “tree (樹).” Totally unexpectedly and for the first time in my life, I realized an inner yearning I had never allowed myself to feel, about the father I could have had, someone I could lean on, who would support me and give me strength. All of these explorations helped me to understand that I couldn’t authentically address large social issues without resolving my own personal ones.

Paradoxically, through playing with material, digging deeper into my own personal issues and truths, and pushing beyond my comfort zone, SFAI became for me a place of larger collaboration and authenticity. This, I believe, is what leads to real change: the ability for artists—predominantly artists of colour, and artists who are not content with the status quo —to uncover our individual truths, to take risks and push the boundaries of acceptability. It is this practice that transcends and will transform the existing culture.

Janet Chan was an SFAI Truth and Reconciliation Resident in October 2018. She is an artist and a multidisciplinary scholar in policing, creativity and the use of IT (including big data and AI) for justice decisions. Initially trained in computer science and applied mathematics, Janet became a scholar in criminology, received her PhD from Sydney University in 1990 and is currently a professor at the Faculty of Law at UNSW Sydney. She studied drawing and painting part-time and was awarded an MFA in 2009 from the College of Fine Arts, UNSW. In her experimental art practice, Janet has explored issues of surveillance and control through technology by using various digital and manual techniques. Since 2014 she has started to work with moving image, sound, poetry and data visualization. Her work has been shown in group exhibitions in Australia and the Netherland, and in academic conferences in Canada and Denmark. She was artist-in-residence at the SEA Foundation in Tilburg and presented a lecture-performance Mapping Crises–Visualising Hope on the international refugee crisis there in October 2017.

POEMS by Janet Chan

The Tree

Your hard bark grates on my forehead

My body follows your contours

Being tied tightly around your trunk

I feel your support

I smell your aroma

I surrender to your structure

Seventy minutes go by – I meditate in silence

as your living cells quietly regenerate

as your roots gently pump moisture into

your branches.

Many years ago a Tree died in the village

His family gathered to mourn

His baby daughter screamed in agony

No one saw her pain

No one smelt her fear

No one came to her rescue

Seventy years went by – she yearned in silence

for some remnants of buried history

for some intimate connection lost in an

incomplete life.

Knitting

A strand of yarn passes over the needle—

only to be guided back as a new

stitch, sitting snugly next to its earlier clone.

A thought passes through my mind—

memories of watching in wonder

dainty dances of fingers, needles, yarn.

Half a century passes since you left—

I feel the spirit and solace you

cleverly conceal in the soft knitted shawl.

Connections

Today we’re all connected—celebrities with

millions of friends and followers joined in

adoration and adulation broadcast in banal

text and endlessly recycled images and gifs.

Bit by bit we get disconnected—atoms with

vanishing links to non-friends left behind through

neglect and negligence crowded out by

interminable screens and shrinking real time.

One day we’ll be connected—survivors with

millions of fellow species wiped out by

apathy and inattention to the warning of

warming, pestilence and rising seas.

© Santa Fe Art Institute / Santa Fe, New Mexico /

© Santa Fe Art Institute / Santa Fe, New Mexico /