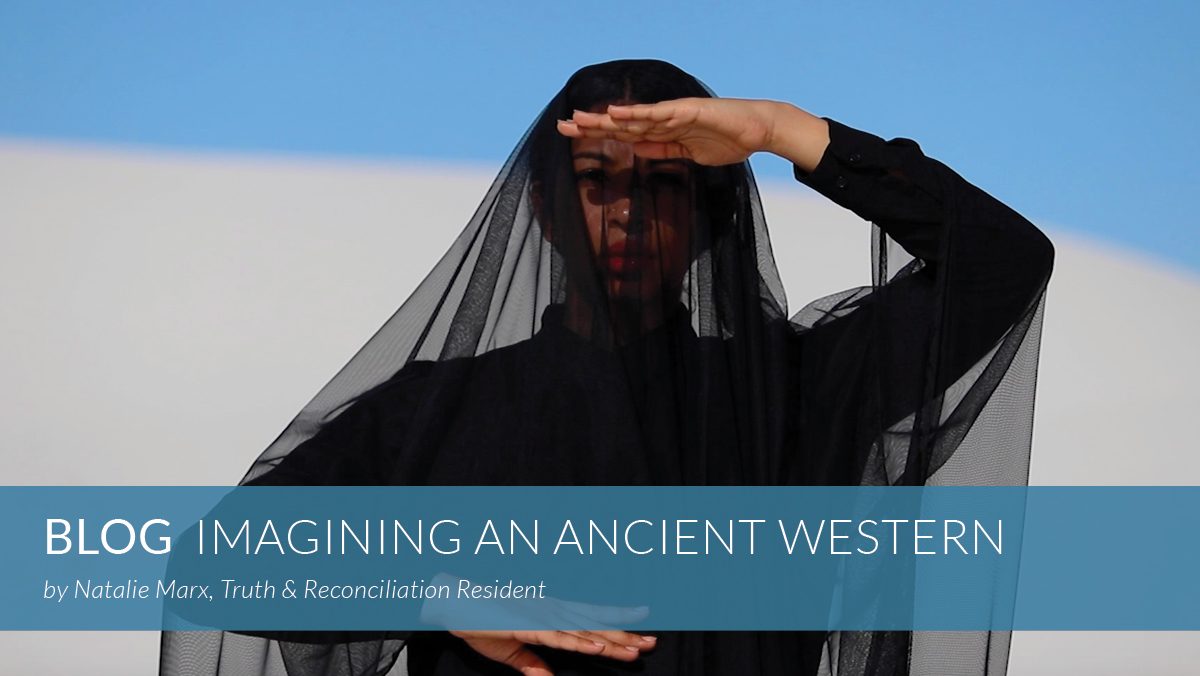

When I first came to SFAI’s Truth & Reconciliation Residency to learn about the local history and write my film essay Muntu Child, I wasn’t fully aware — perhaps due to my fascination for the unfamiliar landscape —that New Mexico was the wild wild west of the old Hollywood films. The films that helped create the dehumanizing image of Native Americans that exists in the culture of the Americas. It wasn’t until I was here | there, facing the breathtaking conflicting beauty of the desert and the histories it contains, that something between the sharp warm sunlight and the breeze traversed my chest and forehead and gave me a vision of time; of clarity. This place is old. The desert is a territory of endurance and transformation, a place of rigor with stories trapped in the gaps of time. The desert is the scenario in which I chose to recreate these moving portraits of my lost ancestors, dreams about the forgotten, the burned books, the familiar gestures, the unwritten books. Something magnificent and emancipatory. In the work, the past spreads in the depth of the picture: blurry lines bring together faces and locations in a suspended moment. An ancient time where I re-imagine my African and Native American ancestors in the splendor of their individual consciousness and civilizations.

During my first residency month and as a result of my explorations on performance and film, I made the short film del muntú with collaborator Leonardo Rúa. In the film, I performed a folk dance from the Carnival of Barranquilla called danza del garabato; a duel dance between the leading dancer of a large group of marching men and women and the character of Death. In the story, the dancer, originally an African slave, fights and defeats the Death. However, invictus, Death reappears the last day of the carnival when the leading party man Joselito suddenly dies turning the celebration into a funeral. Death is always threatening to shorten the live of blackness, is what Haney & Moten suggest in their studies of the undercommons; everyday on the edge, surviving and thriving from the bottom to an abstract identity, to musical savagisms, moving in time in transcendental dances and other “eloquent vulgarities” of blackness. The carnival has a resisting nature, a war resisting nature. We are inseparable from violence because we have been forged by it. In the garabato, life and death dance daily as well as in the desert. Like in western films’ dual wielding sequence, the allegorical confrontation between man/woman and death is the ultimate act that determines the course of individual and collective lives. The cinematographic language is stolen, the image tends to be poor but with monumental dignity. It arouses from a speculation that dares to reclaim|celebrate or die while coding from a form that so artfully discredited us. The work yields a need for conflict resolution, for reparations.

As a Colombian brown woman, I felt obligated to create space for acknowledging the historical, and therefore behavioral, relation of the violence we live in today with the violence of colonization. I created this piece for remembering — I noticed the pile of bodies — and had to stop to mourn the absence of their breath. This is the truth, the horror of a society that treats black and brown bodies as disposable, impacts one’s construction of identity and love. How can we go on? I have come to terms with the fact that reconciliation under the terms of these truths is possible as a radical act of creation. Creation made with our sacred vestiges, with whatever is there that we remember and in spite of the neglect of the State. Artistic expression is a tangible way of creating images of emancipation, creating realities where reparation is possible, resilience is celebrated, memory can cure oblivion, music and dance can preserve the ancestral knowledges and languages that can repair the psychological devastation that ignorance causes in the life of individuals and communities. Representation is important. Remembrance is important. The bill for what’s owed to us is out there. In del muntu the sun, the moon, the marks in the sand, the raw nature became elements of the work. I walked, run, danced in the desert for my people. The diaspora is a rhizome of ancient knowledge embedded in the memory of our bodies, in the dances , the songs, the drums and bells.

This film is a memoir and homage to the disappeared, the never found, the erased, the forgotten, those lost in the depths of the Atlantic ocean, the survivors descendants of Changó. This film is a journey that starts o the coast of Africa, passing through the Caribbean, ending in North of America. Putting into practice the philosophy of the muntu that Manuel Zapata Olivella reveals in his literary work; and using his maps to navigate reincarnations of ancestral spirits through times.

To be able to make Santa Fe a stop in this journey has been a remarkable opportunity. I continue to question while learning from Native American people, what it means to belong to a territory, to care for it. How to create an identity in the present while being on the road, searching on the roots for the places we came from, arriving to new places to share; making artwork with integrity for the memory of our ancestors. This is my hope. I have found collaborators that bring their own journeys into this exploration. The conversations I have had with the artist living in the border and my November SFAI cohort of artist expanded my perspective of how artwork can be a device for the reparation: alive like a garden, colorful, generous, tender and radical.

Santa Fe, see you soon again.

Natalie

The light pours over everything

the cherry tree

the bird landing on my hand

dreams

pains

A divine glow

neglects shadows like a mirror

with the wind the dust voyages

it reminds us where we come from

there is an initial disorientation of solitude

its profound embrace after you surrender

a skull under the sun

certain

the death arrives

The vibrations keep us alive

the drums

sobre la piel

to look into the desert of the lone rider

lost again

lost at last

the savages

the horses

the sunset

the ideals

the land taken

the stolen babies

Damn!

Is a return even possible? For all?

And if we keep going

How do we make sure we don’t forget the way back?

a pulsion that persists through bloods

undeniable call

requires the most radical effort

To be a muntu

to suddenly realize

and fall into the arm-branches of my Yoruba roots

to stop and experience the universes

a system of beliefs that manifest themselves

concretely

every day

with mystery

and splendor

for those who are willing to listen and see

When feeling lost

searching

changing

changing searches

until this stupid transatlantic melancholia

perishes with the winter

a cry is heard from afar

for the lost, the horror

to rest in good deeds

In a bright kitchen

an altar of love

eyes offered me beauty

a vision of myself

a blessing from Oshun

a conceding word

Ashé

© Santa Fe Art Institute / Santa Fe, New Mexico /

© Santa Fe Art Institute / Santa Fe, New Mexico /