Time moves on and change is constant. Reflecting on the city’s growth and urban development, I think back on the time when I was a child. I grew up north of Santa Fe. I saw the town as a special place built for people to enjoy. I recall those days that our family walked around the Plaza, all dressed up for “the city”. We were told to be at our best when we visited our relatives living in Santa Fe. It was normal to hear and speak in both Spanish and English. It was exciting to explore the town and find favorite places. One of mine was the Federal Building and Post Office Park; it had a well-groomed lawn with benches and lots of shade trees. We often picked this serene place to meet our families before driving home. The town had artists living and working on Canyon Road. There were tradesmen and small family businesses. As a teenager, we went up to Canyon Road to explore the area known for art and small family stores. We would drive up to Hyde Park where we built fires, hung out and shared dreams of our futures.

I thought change was good, growth brought new ideas, new art, and people from other places. I expected growth would come to this sleepy little town that visitors often joked about needing a passport to visit. This wasn’t funny to us and I often felt slighted by this objectification. We were different from the people who came to Santa Fe on their family travels to the west. We felt connected to the town, its histories, cultural treasures and the sense of place it offered us.

When I was a teenager, there were no trade schools, junior colleges, or public universities in Santa Fe. I wondered why educational opportunity was a low priority, and I found the need to leave our home to get a better education – an exodus that felt both voluntary and necessary. I look back and wonder if there were other choices for me personally, or for Santa Fe, now known as the City Different. How is Santa Fe different? What perspective influenced the direction Santa Fe would grow and establish its reputation as an artist’s destination? Would this identity determine a path to prepare our community for the future? Would we be a city frozen in time — like a public exhibit? Or would our strong historical and cultural identities govern the pace of growth and limit investment in community development?

I returned to Santa Fe 34 years ago after working as a designer in California, determined to find answers for these questions. I served as Director of City of Santa Fe Planning and Land Use from 2002-2004, and learned a great deal about how our land use policies perpetuate what even then we were calling a housing crisis. As a community – then and now — we have failed to prioritize the well-being of residents and provide sufficient affordable housing to help them secure a higher quality of life. Knowing that economic disparity and inequitable urban design policies both play a major role in Santa Fe’s housing crisis, I wanted to use the Truth and Reconciliation Residency at SFAI to investigate the state of housing in Santa Fe, its effects on residents’ quality of life, and their sense of ownership in their neighborhoods.

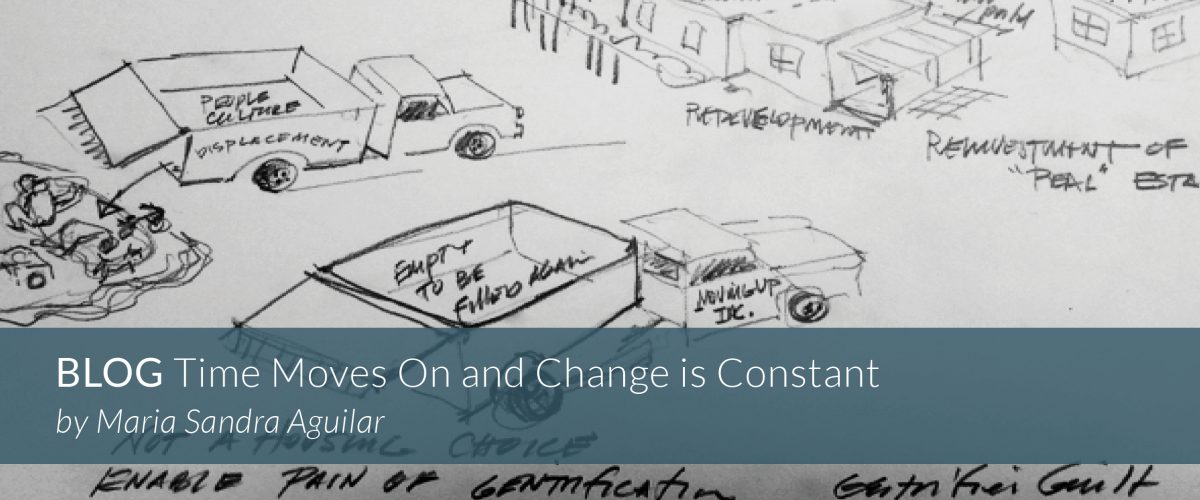

Home ownership is a major economic and social equalizer, stabilizing neighborhoods and encouraging community development. Santa Fe’s housing shortage results in displacement of people and the gentrification of neighborhoods, which creates significant impacts to individuals, families, neighborhoods, and to the community at large. While there are grassroots organizations working to increase housing opportunities , any proposed changes to land use policies seem to encounter resistance by neighborhood advocates who fear change.

The moral challenge for all of us is to shift to prioritizing the residential community’s needs for housing and neighborhood development. Good urban design, good policies, technical capacity, and political will are all critical tools to counter these reactive stances and to allow for the development and implementation of proactive policies that meet the complex needs of all the city’s residents.

Part of a proactive approach requires seeing Santa Fe’s poor and working class people as viable contributing residents, and addressing the great social toll that stems from generations of poverty and lack of educational opportunities. New Mexico ranks 46th in the nation economically, and 50th educationally. A bias toward individualism, which posits that hard work will result in economic prosperity, doesn’t address the complex, underlying causes of intergenerational trauma. It allows shaming the poor. Instead of seeing this as a community crisis we move away from “their problems.”

Urban changes are happening to Santa Fe as in many other cities having to adapt to the new economies we now live in. Expensive properties adjacent to the historic plaza and the historic neighborhoods are available primarily to commercial development and higher income people, which means that long-time residents and multi-generational families are shockingly absent from these neighborhoods. It also means that long-time homeowners in these areas face higher taxes, which combined with high maintenance costs for older homes, often leads to a decision to sell their family homes.

This exodus has large demographic and economic impacts on who can afford to live in Santa Fe. New residents coming from large cities with higher incomes see this as opportunity; long-time residents experience it as displacement. This results in a growing battle, mostly conducted in City Hall skirmishes, that is drawn around social and economic issues, and unfortunately misses the dehumanization that results from this divide.

My desire is to explore possibilities in planning design policies to help reshape Santa Fe residents’ roles in decision making; to find methods of inquiry to help prepare and acquire necessary tools to lead the development as an inclusionary planning process; and to bring all residents to the table that will determine the future of the City’s urban design. This will require honest exchange of life experiences to accept our individual and unique ways of living, our dreams and needs for housing. We renters, homeowners, temporary residents, aging residents, first time parents, people with disabilities, single parent families, extended families — all of us — experience life differently from one another. We have limited opportunity to develop empathy and to see each other’s lives. Instead, in public meetings, we argue about density, parking, noise, size and aesthetics of the structures.

Accessory Dwelling Units (ADUs) are currently at the center of the planning policy debate in Santa Fe. If one sides with the opposition to higher density you are more likely to reject the proposed changes to the code. If one is looking at the possibility of economic benefit and stability that offers an opportunity to remain in your home, you would be in favor of the proposed changes to the code. This type of confrontation between people with different life experiences continues to build ideological walls. The heated discussions are framed in the divisiveness of “us” and “them.” In order to move away from combative positioning and shift toward a more human-centered approach to urban design, we must agree to an honest, inclusionary approach and be willing, as a community for real dialogue.

A new urban design approach will require systemic changes and multi-layered design strategies. We will need to take responsibility for historic, institutional injustices and we will need to commit to process over outcome. This is not an elegant design exercise. This is about engaging in conflict resolution, and hearing differing opinions. We can learn from disparate experiences, confront differences, and build a structural framework for inclusionary policies. The willingness to address inequalities and disparities will require personal conviction by all of us to help move us as a community toward a path of reconciliation.

© Santa Fe Art Institute / Santa Fe, New Mexico /

© Santa Fe Art Institute / Santa Fe, New Mexico /